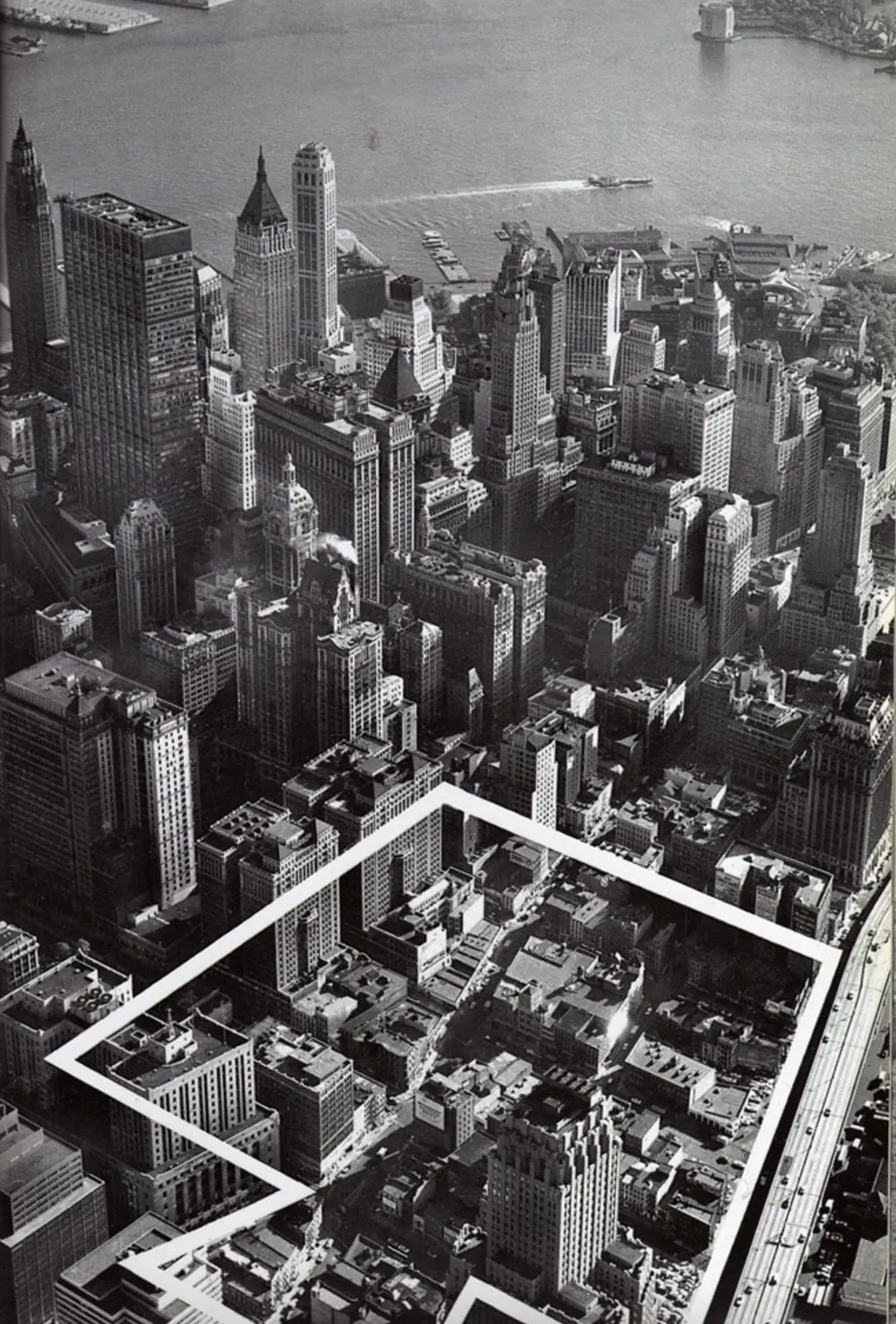

The World Trade Center project was initiated in the early 1960s through the influence of David Rockefeller in part to reclaim a part of the city that had fallen on hard times.

The World Trade Center project was initiated in the early 1960s through the influence of David Rockefeller in part to reclaim a part of the city that had fallen on hard times.

The vision was meant to use the trade facility and urban renewal as tools to clear and revitalize what had become a “commercial slum”.

The construction of the towers yielded not only a new frontier for business but also the landfill for a new shore on the banks of the Hudson.

The project, developed by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey,r was originally planned to be built on the east side of Lower Manhattan, but the New Jersey and New York state governments could not agree on this location.

Original architectural and engineering model. This model is now on permanent display at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.

After extensive negotiations, the New Jersey and New York state governments agreed to support the World Trade Center project, which was built at the site of Radio Row in the Lower West Side of Manhattan, New York City.

After a search that engaged dozens of architects and many months, Yamasaki’s firm, of Troy Michigan, was chosen as the design architect and Emery Roth & Sons as associate architects for the assemblage of buildings that were to comprise 5 of the buildings within the World Trade Center complex, including both towers.

At the time, Yamasaki was part of a loose grouping of architects that attended to the needs of the new ideas of urban renewal and mixed-use megadevelopment.

His use of primary forms and simple ornamentation allowed for the functional needs of the new and often very large forms of low-income housing projects and the new and ever-larger office buildings being commissioned by American and multi-national corporations.

He was well enough known in 1963 to be chosen for the cover of Time magazine. At the same moment, he was much criticized for his almost servile attendance to the needs of large corporations.

And yet, Yamasaki brought a certain sensitivity of material and form that had been missing from previous proposals for the World Trade Center site.

His words were often self-deprecating, humorous, and displayed an interest in pursuing a personal vision for a new architecture; even amid the gigantic scale of the forms he was designing.

While Yamasaki espoused a conservative architecture of uncompromising modernism, his aesthetic was neither overly harsh nor dogmatic.

He favored materials of a softer, gentler feel; woods, smooth and painted concrete, stainless steel, and anodized aluminum plate. His buildings often bore hints of a renewed interest in ornament and figurative form as part of new modernism.

Yamasaki’s final design for the World Trade Center was unveiled to the public on January 18, 1964, with an eight-foot model.

The towers had a square plan, approximately 207 feet (63 m) in dimension on each side.

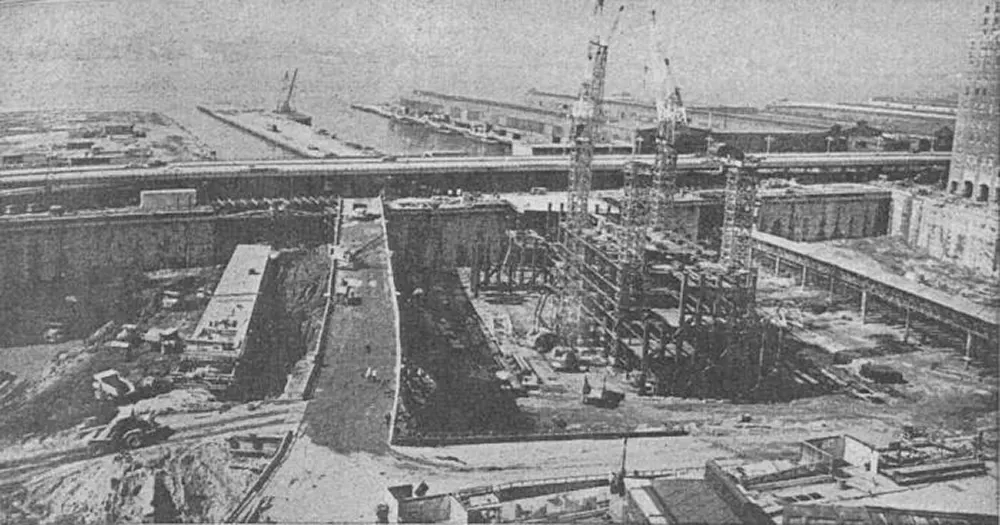

Excavation of the World Trade Center site, as seen in 1968.

The buildings were designed with narrow office windows, only 18 inches (45 cm) wide, which reflected Yamasaki’s fear of heights and desire to make building occupants feel secure.

The windows only covered 30% of the buildings’ exteriors, making them look like solid metal slabs from a distance, though this was also a byproduct of the structural systems that held up the towers.

Yamasaki’s design called for the building facades to be sheathed in aluminum alloy.

The World Trade Center design brought criticism of its aesthetics from the American Institute of Architects and other groups.

Lewis Mumford, author of The City in History and other works on urban planning, criticized the project and described it and other new skyscrapers as “just glass-and-metal filing cabinets.”

The building of the towers was an endeavor at the scale of municipal infrastructure. Five streets were closed and clearance of the site provided 16 acres for the new project.

Two subway lines on the site were kept running as the foundations and basements were built around them.

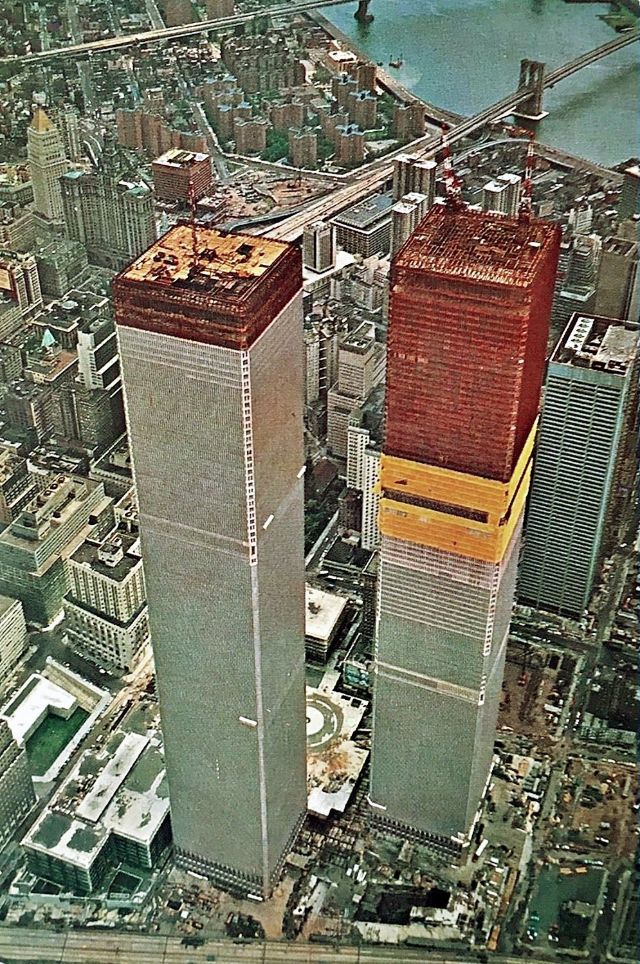

Construction began in 1965 and it was formalized with a groundbreaking ceremony on August 5, 1966, and finally completed with the occupation of Tower One in 1970 and Tower Two in 1972.

In total, the entire complex contributed to Lower Manhattan more than 10 million square feet of office space, several hundred hotel suites, the most successful retail center in the city, an extremely busy transportation hub, and dozens of service and support businesses in seven buildings.

The construction of the towers was a unique engineering challenge from the very beginning.

With the excavation of the foundations, the construction team had to find solutions to problems never before encountered at such a scale.

With the use of slurry walls, the first time this type of foundation wall was used in the US, the construction had to proceed through highly creative solutions of materials handling, erection sequencing, joint detailing, structural engineering, and architectural design.

The foundations for the towers reached down to bedrock an average of 70 feet below grade.

The foundations for the towers reached down to bedrock an average of 70 feet below grade.

With the excavation of 1.2 million cubic yards of earth, 23.5 acres of new land for Manhattan were created on the shores of the Hudson River.

Eventually, the office towers and wintergarden of the World Financial Center, designed by Cesar Pelli, and several apartment buildings were built on this new land.

The material expenditures on the towers were enormous; 192,000 tons of steel, 425,000 cubic yards of concrete, 43,600 windows with 572,000 square feet of glass, 1,143,000 square feet of aluminum sheet, 198 miles of ductwork, and 12,000 miles of electrical cable.

The material expenditures on the towers were enormous; 192,000 tons of steel, 425,000 cubic yards of concrete, 43,600 windows with 572,000 square feet of glass, 1,143,000 square feet of aluminum sheet, 198 miles of ductwork, and 12,000 miles of electrical cable.

The towers also provided an extraordinary employment opportunity for the construction workers of the region. More than 3,500 people were employed continuously on-site during construction.

A total of 10,000 people were involved in its construction. Tragically, 60 people were killed during construction.

During their lifetimes the towers were host to the birth of 17 babies and 19 murders.

During their lifetimes the towers were host to the birth of 17 babies and 19 murders.

Fifty thousand people called the towers their place of work and on many days tens of thousands visited.

In 1993, the towers were attacked by terrorists who entered an underground garage and detonated a bomb that did substantial damage to several floors of the garage but left the towers intact.

The bomb was extremely powerful containing 1200 pounds of urea nitrate. Six people were killed.

On September 11, 2001, terrorists attacked the towers using two airliners to crash into and cause the collapse of both buildings. Each building was struck at a different height and angle.

On September 11, 2001, terrorists attacked the towers using two airliners to crash into and cause the collapse of both buildings. Each building was struck at a different height and angle.

The preliminary analysis seems to indicate that the two suffered damage in different areas of the exterior wall and core and, as a result, their individual progressive collapse mechanisms were also distinct.

In the end, each tower was felled by the initiation of a critical progressive collapse that toppled each building in a near free-fall condition.

World Trade Center under construction, 1970.

Aerial view from lower West Side with new World Trade Center’s Twin Towers (fore) against the background of Manhattan, 1971.

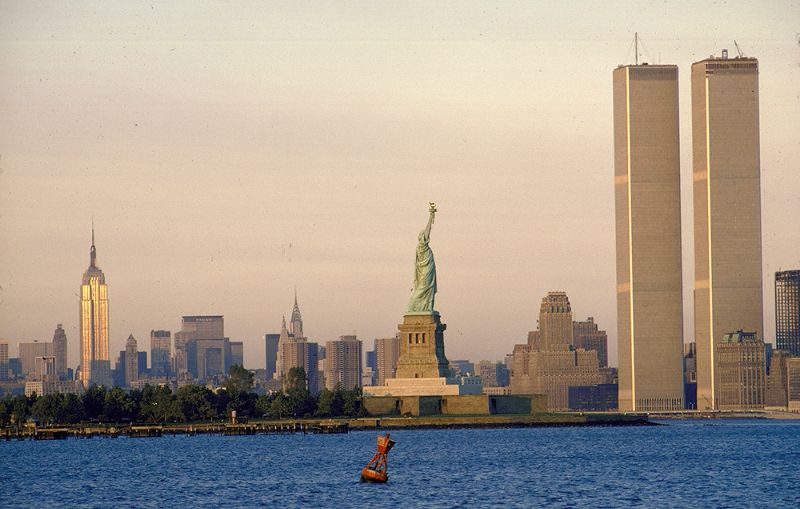

The World Trade Center, 1971. (Photo by Peter J. Eckel).

New York at night, 1972.

A view of lower Manhattan, New York City seen from a ferry, 1973. (Photo by Peter J. Eckel).

The Empire Building overshadowed, 1973

A late afternoon view of the NYC skyline including the unfinished World Trade Center from the wasteland which used to exist where Morris Canal Park is now. Fall 1972. (Photo by Andy Blair).