A policeman directs buses in the intersection of Trafalgar Square, London.

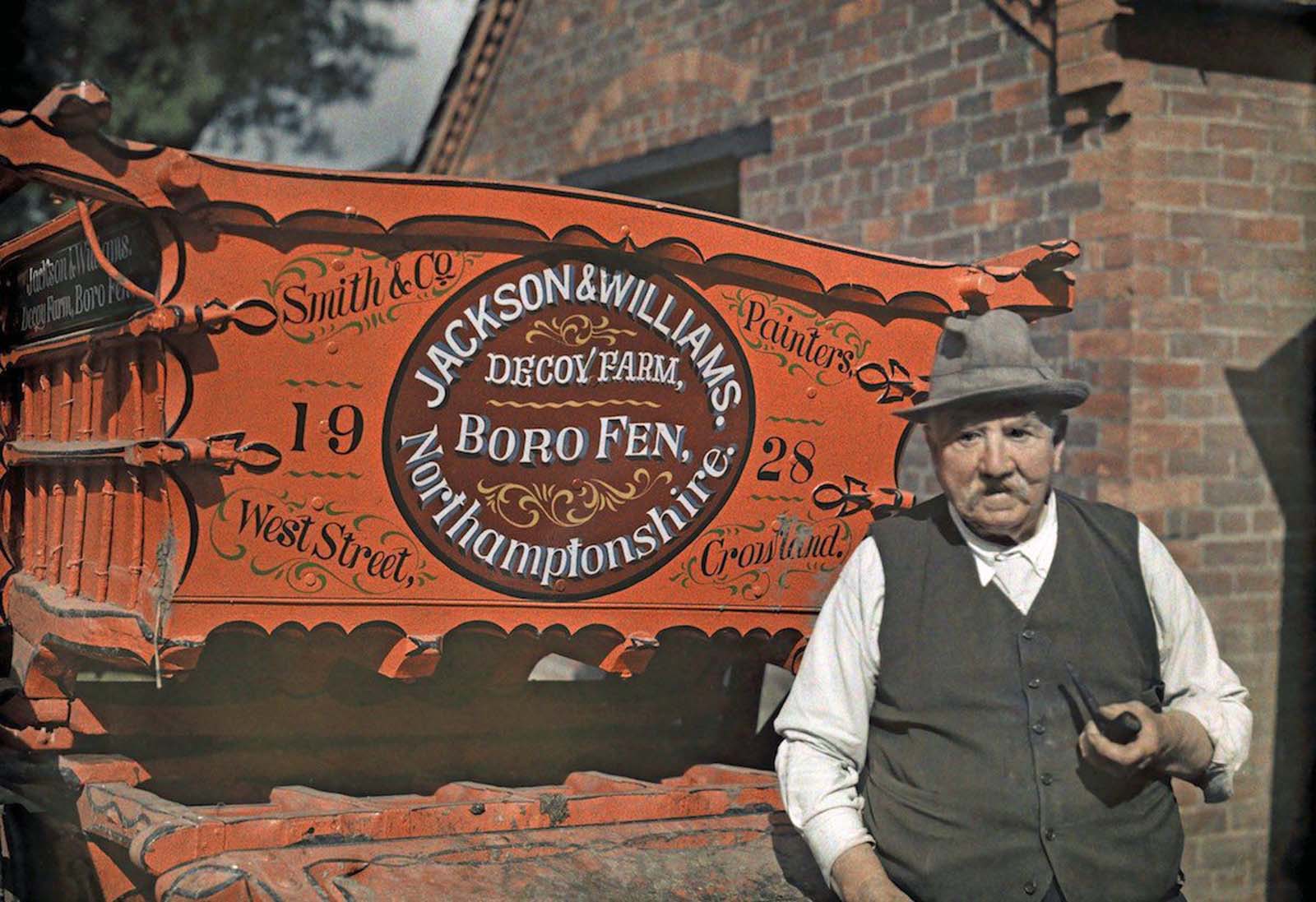

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, photographer Clifton R. Adams was commissioned by the National Geographic to document life in England.

Adams’ beautiful autochromes—a process of producing color images by using potato starch—present images that capture the last of an England that was slowly heading towards modernity.

Adams, who died in 1934, was instructed to record its farms, towns and cities, and its residents at work and play.

The color images were produced using the Autochrome Lumière, which was the most advanced color photographic process of the day.

The plates were covered in microscopic potato starch grains colored red, green, and blue-violet, with about four million per square inch.

An English woman points pridefully to her farm cart, in Cambridgeshire, England. Wicks of Wisbech constructed horse-drawn caravans used by Romany families traveling throughout Britain.

The gaps between the grains filled with lampblack, and the coated layer allowed the exposure to capture a color image.

The light passed through the color filters when an image was taken, with the plate then processed to produce positive transparency.

The 1920s was a decade of contrasts. The First World War had ended in victory, peace had returned and with it, prosperity. This was a transitional period between two kinds of society and two economies.

An informal portrait of a farmer and his cart, in Crowland, Lincolnshire. Decoy Farm is now the site of a recycling centre and a housing estate.

There was a depression yet generally living standards were rising. Steam power was gradually replaced by electricity. Transport became petrol engine powered.

Early plastics were often used instead of basic metals and man-made fibers such as regenerated rayon, called artificial silk (known as art silk) were increasingly supplementing cotton and silk.

The resultant expansion of the chemical industry created jobs which helped the economy change from the domination of the heavy industry.

A police constable passes the day with farmers gathering hay, in Lancashire.

The position of women in Britain was changing. In 1918 after the war ended women over 30 were given the vote if they were householders. By 1928 all women over 21 were given the vote.

Even so, a patronizing attitude toward women still existed and women were in some circles still regarded as the decorative appendages of men with no other purpose but to bear children.

Slowly women were breaking down old attitudes. The war had given ordinary working women an alternative to domestic employment.

They found they liked working on the land, in factories, and on buses. Families were of a smaller size compared to those in Victorian families while children were educated until the age of fourteen.

Two women rest for lunch in a Lancashire hayfield.

In 1921 the Education Act raised the school leaving age to 14. State primary education was now free for all children and started at age 5; even the youngest children were expected to attend for the full day from 9 am to 4.30 pm.

In the country, pupils at some schools were still practicing writing with a tray of sand and a stick, progressing to a slate and chalk as they became more proficient.

A young girl plays in the sand at Sandown, Isle of Wight.

Classes were large, learning was by rote, and books were shared between groups of pupils, as books and paper were expensive. Nature study, sewing, woodwork, country dancing, and traditional folk songs were also taught.

From a decade that started with such a ‘boom’, the 1920s ended in an almighty bust, the likes of which weren’t to be seen again for another eighty years.

Actors dress for a pageant as Britannia and her knights.

The characters of Britannia and her colonies and dependencies, in Southampton, Hampshire.

Two women buy ice cream from a vendor out of his converted car, in Cornwall. Kelly’s ice cream is still in production today.

A woman sticks her head out of her bridge house window, in Ambleside, Lake District, Cumbria, England.

A war veteran sells matches on the street, in Canterbury, Kent.

A young girl sells artificial flowers for charity on Alexandra Day, in Kent. The first Alexandra Rose Day was held in 1912; it commemorated the arrival in Britain of Princess Alexandra of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, from Denmark, in 1862. She was betrothed to Prince Edward, later King Edward VII, and they married the next year. Her admirers wished to mark the 50th anniversary of her arrival and she proposed marking it by the sale of paper roses in aid of her favourite charities. The day became an annual occasion.

Women selling Queen Alexandra roses for charity, in Seaford, East Sussex.

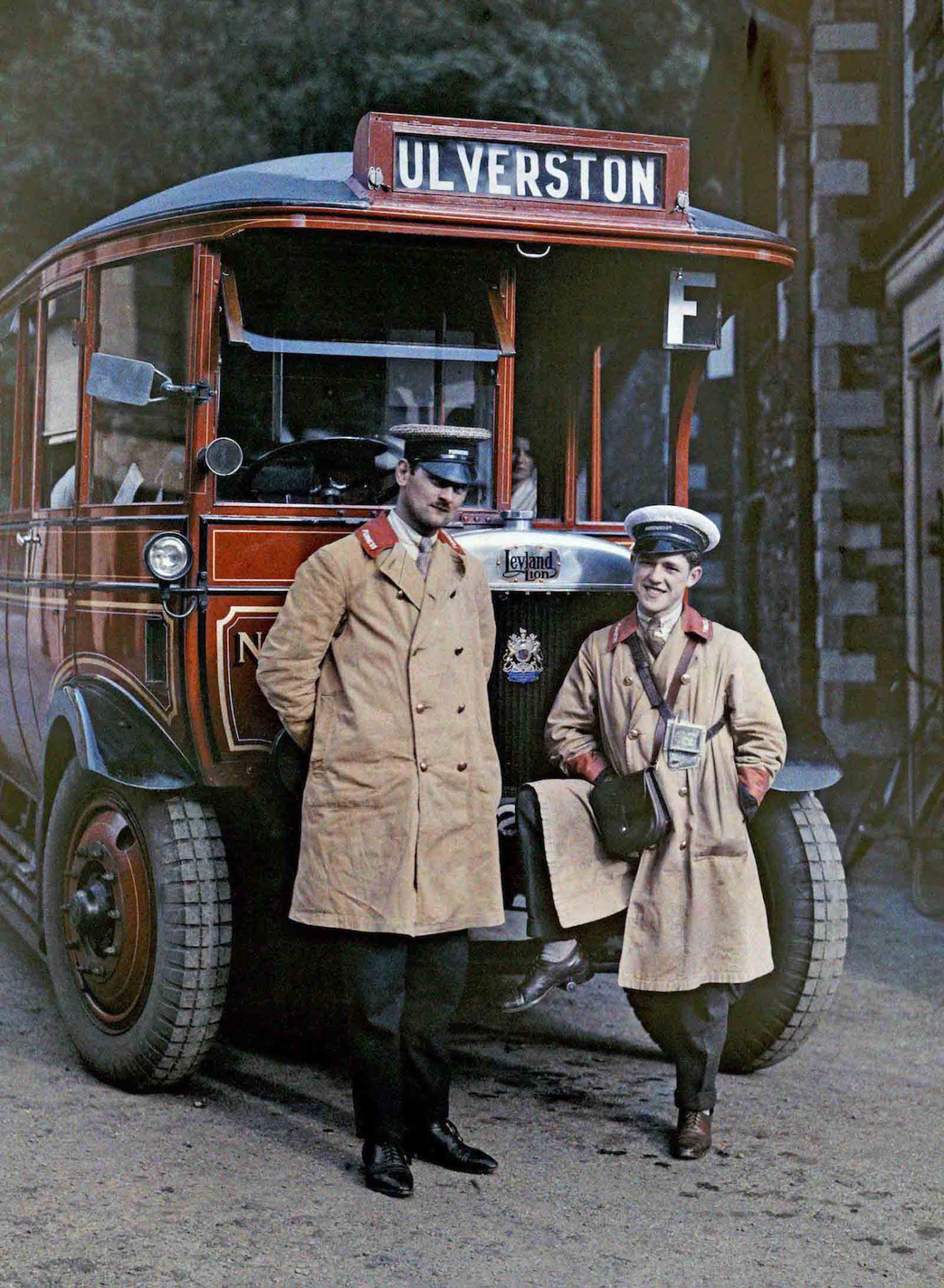

Two bus drivers stand in front of a tour bus in Ulverston, Cumbria.

In Oxford, the corner of High street and Carfax is bustling.

A view of the Cunard SS “Mauretania” at dock, in Southampton, Hampshire.

A view of a vine-covered house on a Stratford-upon-Avon street, in Warwickshire.

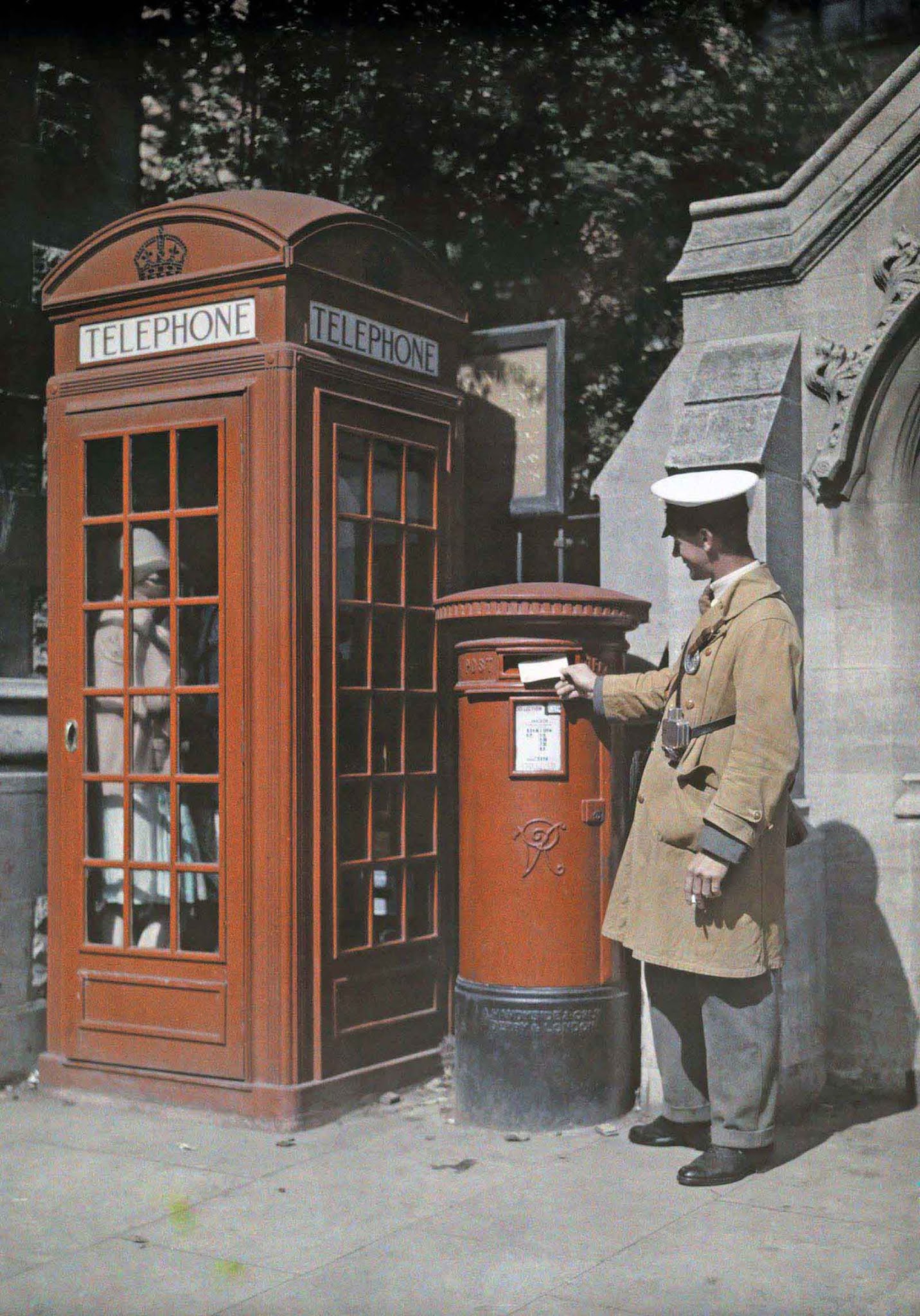

A young woman mails a letter at the pillar box, in Oxford.

Women have tea in front of the Clock House, originally a hospice, in Buckinghamshire.

A little boy mails a letter in the hedgerow, in Sussex.

A London double-decker bus stops to allow people aboard.

Two girls send a letter at a red pillar box in Belfast in 1927.

A group of women hike in Cumbria.