Its unique triangular shape and architectural significance have made it an icon of the city’s rich history and cultural heritage.

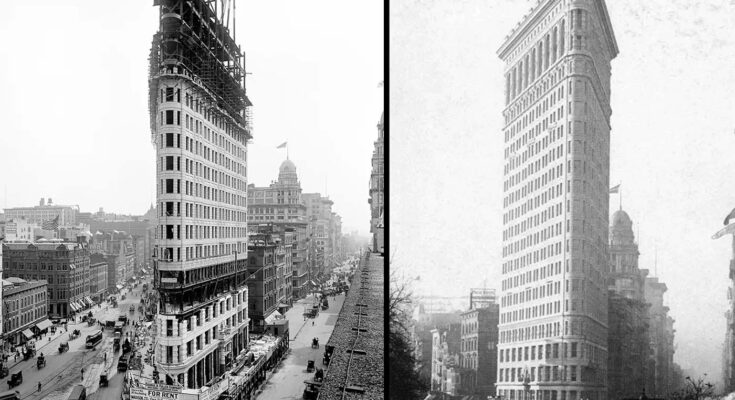

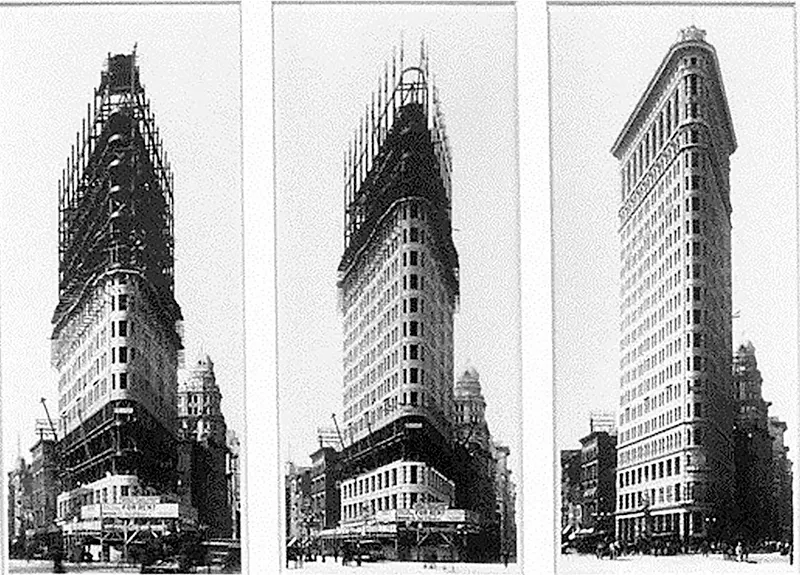

In this article, we will take a journey back in time and explore the history of the Flatiron Building through a collection of old images and photographs that showcase its construction, development, and evolution over the years.

Designed by Daniel Burnham and Frederick P. Dinkelberg, the Flatiron Building was completed in 1902 and originally contained 20 floors.

Designed by Daniel Burnham and Frederick P. Dinkelberg, the Flatiron Building was completed in 1902 and originally contained 20 floors.

The building sits on a triangular block formed by Fifth Avenue, Broadway, and East 22nd Street—where the building’s 87-foot (27 m) back end is located—with East 23rd Street grazing the triangle’s northern (uptown) peak. The name “Flatiron” derives from its triangular shape, which recalls that of a cast-iron clothes iron.

The Flatiron Building was developed as the headquarters of construction firm Fuller Company, which acquired the site from the Newhouse family in May 1901.

Construction proceeded at a very rapid pace, and the building opened on October 1, 1902. A “cowcatcher” retail space and a one-story penthouse were added shortly after the building’s opening.

The Fuller Company sold the building in 1925 to an investment syndicate. The Equitable Life Assurance Society took over the building after a foreclosure auction in 1933 and sold it to another syndicate in 1945.

Helmsley-Spear managed the building for much of the late 20th century, renovating it several times. The Newmark Group started managing the building in 1997. The building’s ownership was divided among several companies, which started renovating the building again in 2019.

Similar to the parts of a classical Greek column, the Flatiron Building’s facade is divided into a base, shaft, and capital.

Similar to the parts of a classical Greek column, the Flatiron Building’s facade is divided into a base, shaft, and capital.

The Fifth Avenue and Broadway elevations of the facade are both eighteen bays wide, while the 22nd Street elevation is eight bays wide; the bays are arranged in pairs.

The southwest and southeast corners are curved, with one rounded window on each story above the base. In addition, each story of the curved prow on 23rd Street contains three sash windows; the central window is wider than the other two. Many of the Flatiron Building’s tenants referred to the prow as “the Point”.

The facade of the three-story base is made of limestone. Each of the openings at the base is two bays wide. There are entrances on either end of the 22nd Street elevation, as well as at the centers of the Fifth Avenue and Broadway elevations.

The facade of the three-story base is made of limestone. Each of the openings at the base is two bays wide. There are entrances on either end of the 22nd Street elevation, as well as at the centers of the Fifth Avenue and Broadway elevations.

Above the base, the facade is made of glazed terracotta from the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company in Tottenville, Staten Island. The building also contains decorative details such as cornices, moldings, and oriel windows.

These materials were intended to give the impression of “general unity in treatment”, while also giving the facade a textured appearance.

The building was considered to be “quirky” overall, with drafty wood-framed and copper-clad windows, no central air conditioning, a heating system which utilized cast-iron radiators, an antiquated sprinkler system, and a single staircase should evacuation of the building be necessary.

The building was considered to be “quirky” overall, with drafty wood-framed and copper-clad windows, no central air conditioning, a heating system which utilized cast-iron radiators, an antiquated sprinkler system, and a single staircase should evacuation of the building be necessary.

The offices were furnished with mahogany and oak, which the Fuller Company advertised as “fireproof”. The triangular shape of the structure led to a “rabbit warren” of oddly-shaped rooms.

The offices on each floor were connected by a central passageway, and each floor contained about 20 office cubicles, all of which were connected by various doors.

According to The New York Times, offices in the prow had “impressive” views “because of the converging traffic street markings, which accent the telescoping boulevards, and because of the changing seasons in Madison Square Park”.

The building contained its own power plant, which generated high-pressure steam and electricity. In the 1940s, it was one of the few remaining structures in New York City with its own power plant.

Bathrooms for males and females are placed on alternating floors, with the men’s rooms on even floors and the women’s rooms on odd ones. Originally, there were no restrooms for women.

The construction of the Flatiron Building was a major feat of engineering, with the building’s triangular shape and height presenting a number of technical challenges.

The construction of the Flatiron Building was a major feat of engineering, with the building’s triangular shape and height presenting a number of technical challenges.

The building’s steel frame had to be reinforced with diagonal bracing to ensure its stability, while its triangular shape required the use of specialized materials and construction techniques.

One of the biggest challenges faced by the architects was the building’s proximity to the subway tunnels that ran beneath it. The construction of the building caused the subway tunnels to shift, leading to concerns about the safety of the subway system.

To address this issue, the architects had to design a complex system of underpinning and support beams to stabilize the building and prevent any further shifting of the subway tunnels.

The Flatiron Building became an icon of New York City upon completion, and public response to it was enthusiastic. The structure attracted not only “sidewalk superintendents” – members of the general public who expressed great interest in the project – but also architects and engineers.

The Flatiron Building became an icon of New York City upon completion, and public response to it was enthusiastic. The structure attracted not only “sidewalk superintendents” – members of the general public who expressed great interest in the project – but also architects and engineers.

Crowds of several hundred people looked at the building “for five and ten minutes at a time”, often from multiple vantage points, while the Tribune said that crowds would sometimes look at the building “with their heads bent back until a general breakage of necks seems imminent”.

By the mid-20th century, the building no longer attracted crowds, and most tourists “want[ed] to go up in the Flatiron only to take pictures of other taller buildings”.

However, it remained well known, even after taller buildings such as the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building were constructed.

According to graphic designer Miriam Berman, the building’s enduring popularity was attributed to the fact that it was “the only famous Manhattan skyscraper that enables tourists to take a picture of the entire building from the ground up”.

Construction phases.

Unlike other structures, such as the Seagram Building or New York City’s brownstone houses, the Flatiron Building’s shape was rarely copied by other structures in the city until the early 21st century.

This was in part because many buildings occupied rectangular sites on Manhattan’s street grid; furthermore, developers tended to avoid buying oddly-shaped plots, as their unconventional dimensions were hard to market to potential tenants.

Consequently, in the early 20th century, the Flatiron Building was one of only two major buildings that were developed at the intersection of Broadway and another north–south avenue; the other was the Times Tower.

Although some buildings in lower Manhattan, such as One Wall Street Court, also contain a flatiron shape, they generally were not as well known as the Flatiron Building.

The site of the Flatiron Building prior to its construction.

The building c. 1903.

After the end of World War I, the 165th Infantry Regiment passes through the Victory Arch in Madison Square, with the Flatiron Building in the background, 1919.