.jpg) The Islamic Republic imposes strict rules on Iranian life. This extended photo collection shows Iranian society prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution and, it’s obvious that Iran was a very different world.

The Islamic Republic imposes strict rules on Iranian life. This extended photo collection shows Iranian society prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution and, it’s obvious that Iran was a very different world.

It was also a world that was looking brighter for women. And, as everyone knows, when things get better for women, things get better for everyone. After the revolution, the 70 years of advancements in Iranian women’s rights were rolled back virtually overnight.

The 1979 revolution, which brought together Iranians across many different social groups, has its roots in Iran’s long history.

These groups, which included clergy, landowners, intellectuals, and merchants, had previously come together in the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–11.

Efforts toward satisfactory reform were continually stifled, however, amid reemerging social tensions as well as foreign intervention from Russia, the United Kingdom, and, later, the United States.

The United Kingdom helped Reza Shah Pahlavi establish a monarchy in 1921. Along with Russia, the U.K. then pushed Reza Shah into exile in 1941, and his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi took the throne.

In 1953, amid a power struggle between Mohammed Reza Shah and Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the U.K. Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) orchestrated a coup against Mosaddegh’s government.

.jpg)

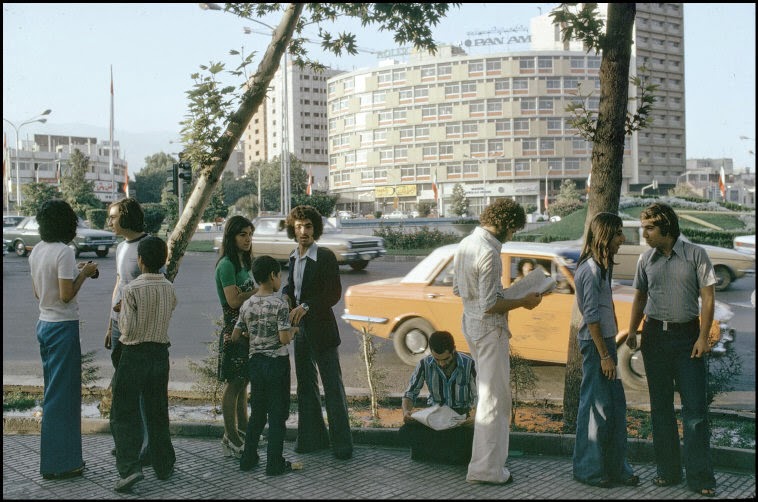

Queen Elizabeth Boulevard in 1971.

Years later, Mohammad Reza Shah dismissed the parliament and launched the White Revolution—an aggressive modernization program that upended the wealth and influence of landowners and clerics, disrupted rural economies, led to rapid urbanization and Westernization, and prompted concerns over democracy and human rights.

The program was economically successful, but the benefits were not distributed evenly, though the transformative effects on social norms and institutions were widely felt.

Opposition to the shah’s policies was accentuated in the 1970s, when world monetary instability and fluctuations in Western oil consumption seriously threatened the country’s economy, still directed in large part toward high-cost projects and programs.

A decade of extraordinary economic growth, heavy government spending, and a boom in oil prices led to high rates of inflation and the stagnation of Iranians’ buying power and standard of living.

.jpg)

Entrance to Tehran University in 1971.

In addition to mounting economic difficulties, sociopolitical repression by the shah’s regime increased in the 1970s.

Outlets for political participation were minimal, and opposition parties such as the National Front (a loose coalition of nationalists, clerics, and non-communist left-wing parties) and the pro-Soviet Tūdeh (“Masses”) Party were marginalized or outlawed.

The social and political protest was often met with censorship, surveillance, or harassment, and illegal detention and torture were common.

For the first time in more than half a century, the secular intellectuals—many of whom were fascinated by the populist appeal of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a former professor of philosophy in Qom who had been exiled in 1964 after speaking out harshly against the shah’s recent reform program—abandoned their aim of reducing the authority and power of the Shiʿi ulama (religious scholars) and argued that, with the help of the ulama, the shah could be overthrown.

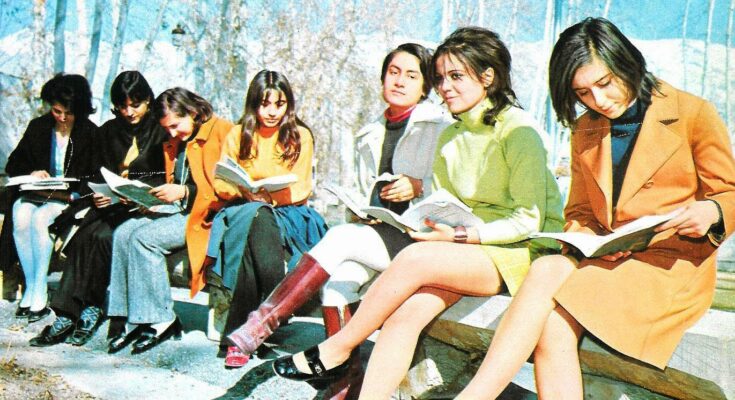

.jpg)

Tehran university students in 1971.

In this environment, members of the National Front, the Tūdeh Party, and their various splinter groups now joined the ulama in broad opposition to the shah’s regime.

Khomeini continued to preach in exile about the evils of the Pahlavi regime, accusing the shah of irreligion and subservience to foreign powers.

Thousands of tapes and print copies of Khomeini’s speeches were smuggled back into Iran during the 1970s as an increasing number of unemployed and working-poor Iranians—mostly new migrants from the countryside, who were disenchanted by the cultural vacuum of modern urban Iran—turned to the ulama for guidance.

The shah’s dependence on the United States, his close ties with Israel—then engaged in extended hostilities with the overwhelmingly Muslim Arab states—and his regime’s ill-considered economic policies served to fuel the potency of dissident rhetoric with the masses.

.jpg)

Iranian university students in the 1970s.

Outwardly, with a swiftly expanding economy and a rapidly modernizing infrastructure, everything was going well in Iran.

But in little more than a generation, Iran had changed from a traditional, conservative, and rural society to one that was industrial, modern, and urban.

The sense that in both agriculture and industry too much had been attempted too soon and that the government, either through corruption or incompetence, had failed to deliver all that was promised was manifested in demonstrations against the regime in 1978.

Amidst massive tensions between Khomeini and the Shah, demonstrations began in October 1977, developing into a campaign of civil resistance that included both secular and religious elements.

The protests rapidly intensified in 1978 as a result of the burning of Rex Cinema which was seen as the trigger of the revolution, and between August and December of that year, strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country.

.jpg)

Medical students at Tehran University.

On 16 January 1979, the Shah left Iran and went into exile as the last Persian monarch, leaving his duties to a regency council and Shapour Bakhtiar, who was an opposition-based prime minister.

Ayatollah Khomeini was invited back to Iran by the government, and returned to Tehran to a greeting by several thousand Iranians.

The royal reign collapsed shortly after, on 11 February, when guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed troops loyal to the Shah in armed street fighting, bringing Khomeini to official power.

Iranian people voted in a national referendum to become an Islamic republic on 1 April 1979 and to formulate and approve a new theocratic-republican constitution whereby Khomeini became the supreme leader of the country in December 1979.

.jpg)

Miss Iran 1967, Shahla Vahabzadeh.

The revolution was unusual for the surprise it created throughout the world. It lacked many of the customary causes of revolution (defeat in war, a financial crisis, peasant rebellion, or disgruntled military).

Moreover, it occurred in a nation that was experiencing relative prosperity; produced profound change at great speed; was massively popular; resulted in the exile of many Iranians.

The Revolution replaced a pro-Western secular authoritarian monarchy with an anti-Western Islamist theocracy based on the concept of velayat-e faqih (or Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists) straddling between authoritarianism and totalitarianism.

.jpg)

The Tehran Twist: The Tehran jet-set entertaining themselves with rock and roll music in the early 1960s.

Declaring himself Allah’s own messenger, Ayatollah Khomeini’s vision for Iran was a return to conservative Islamic values and a purge of Western influences.

This involved a radical reinterpretation of Islamic social guidelines and a regression to religious standards practiced over a thousand years ago. The modest rights women had achieved under the Shaw were summarily revoked by Khomeini.

Professional women were fired in masse and encouraged to take up household duties, caring for children and husbands. Quickly, every aspect of female life was brought under strict government control.

New laws were passed banning Western clothing and requiring that women remain completely covered by a traditional Islamic hijab in public at all times. No hair could be visible; no open-toed shoes.

A special government agency was created to enforce the moral dress code; the Prevention of Vice and Enjoining of Virtue Center dealt exclusively with women found to be in violation of the dress code in any way.

The military training of the revolutionary guards was expanded to include spotting imperfections in the dress code and policing women.

.jpg)

Old men amusing themselves with water pipes on Isfahan street in the 1960s.

.jpg)

Mother shopping for her young son in the children’s section of a Tehran department store in 1971.

.jpg)

A Tehran hospital operating room in 1971.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)